Back to blog

Education

December 3, 2025

Physics and the Liberal Arts

New Saint Andrews College recently began offering a physics colloquium to run alongside the natural history course. NSA students, typically juniors, now choose between the two offerings in order to satisfy their science requirement—though one could, of course, take both while at NSA. Since natural history has been a fixture of the curriculum for years, many in the NSA community are familiar with it. Physics, by contrast, is less known. What is it about?

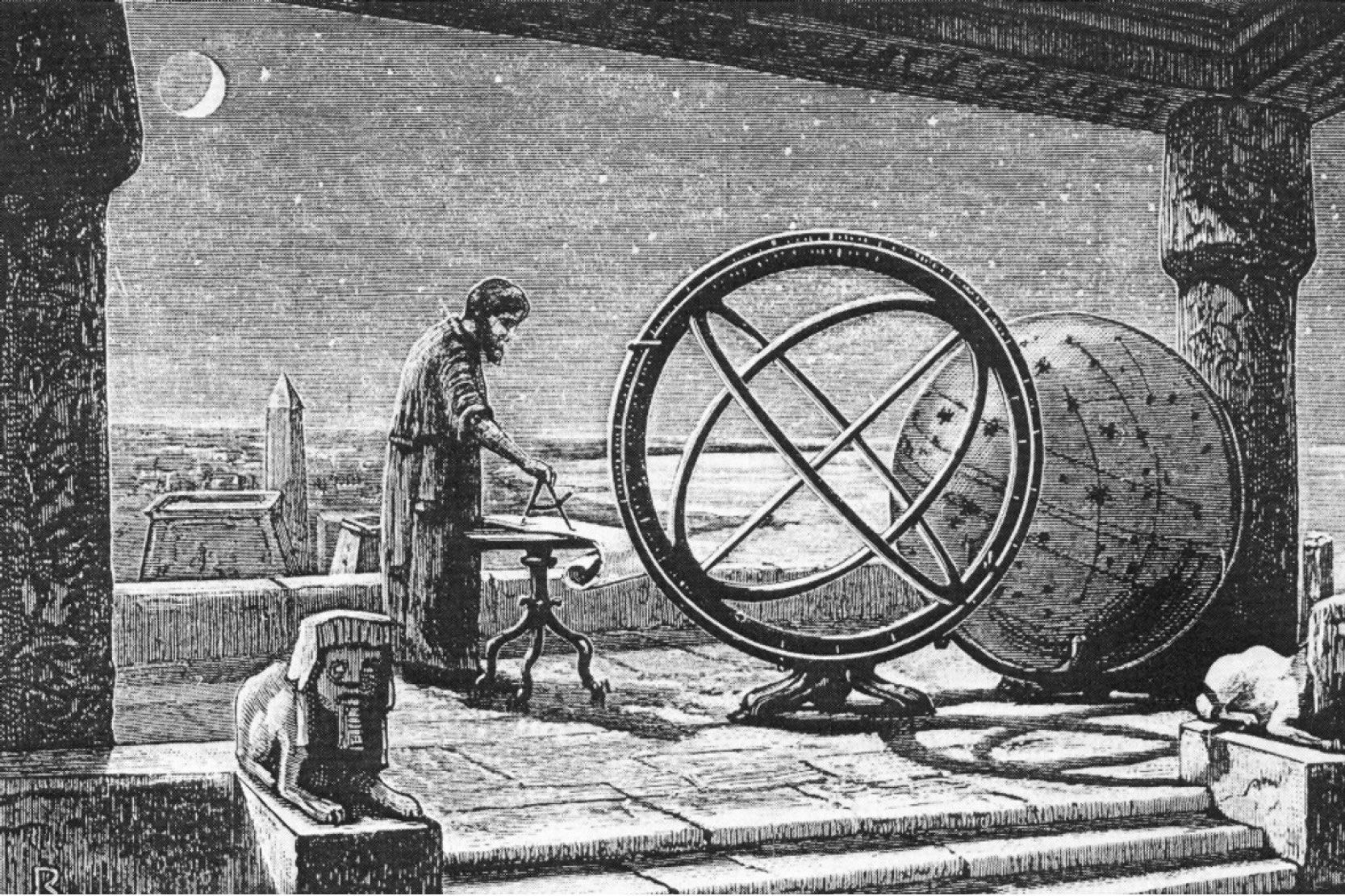

The physics colloquium is designed to introduce students to the Western tradition of physical science. ‘Physics’ therefore should be understood in a broad sense to refer to a collection of disciplines spanning astronomy, cosmology, physics proper, and chemistry. Students learn how these disciplines influence one another—how classical, Newtonian mechanics was ironed out initially as an astronomical theory, or how chemical concepts of the 19th century were eventually explained, in the early 20th century, by physicists’ theory of the nuclear atom. This broad construal of physics helps to capture the two primary domains with which physical science has been concerned since its inception in Ancient Greece: the large and the small. Beginning with the introduction of theoretical thinking in Greece, the tradition has sought accounts of both the large-scale structure of the cosmos as a whole and also a small-scale theory of matter designed to account for the constitution of things. Physical science therefore pertains to cosmological and constitutional questions. One sees, for example, the first sophisticated attempt to answer both kinds of questions in Plato’s Timaeus, the first science textbook. The scope of the course is, in part, set by both this broad understanding of physics and its proper domains.

The colloquium is also structured historically. It introduces students to the Western tradition of physical science, not just the eventual winners. That means that we study theories and ideas that have since been shown to be false, but also the ones that are true (or at least better than the others). There are many reasons for this. By studying the history of physics, we deepen our grasp of the Western intellectual tradition, which has been shaped by physics to an inestimable extent. If we pick up Immanual Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, for example, we find him discussing Galileo, and he assumes that we know what he is talking about. If we read Descartes’ Meditations without realizing that his main project was one in physics—as he himself said—then we miss his real purpose and misconstrue him. If we can only describe Einstein as that really nerdy guy with crazy hair, we miss a major movement of the 20th century and Einstein’s genteel grooming.

"A student coming out of the physics colloquium should be able to articulate where physics currently stands, and he should be able to tell a story as to how we got here, from Ancient Greece to today."

We should also like to know why certain theory changes occur. This is tantamount to knowing why one theory is accepted and a competing theory rejected. More often than not, a competition between theories arises when an older theory is challenged by a newer one, thus necessitating a historical outlook when one wants to understand theory change. A series of pertinent questions arise. What phenomena are these theories trying to account for? What are they trying to explain? What is the experimental or observational evidence that speaks in favor of theory A and against theory B? What makes theory A better than theory B anyway—just the experimental evidence, or the loudness of its proponents, or something else? By answering these questions, and others like them, students are trained to discern scientific arguments, and that is a general skill that can be applied to whatever theories A and B one might run up against. Scientific ideas change, and you have to know how to deal with it. The alternative is to be a sidelined spectator.

But to not be sidelined, students also have to learn scientific concepts. Learning scientific concepts requires two distinct approaches. To the greatest extent possible, we should first like to be able to do physics—that is, to be able to manipulate and apply the mathematical formulae that make up a theory. There is never a full-blown substitute for this skill when it comes to showing conceptual understanding, and therefore the physics colloquium will always feature some measure of mathematical tinkering. Nevertheless, one of the main goals of the physics course is to familiarize students with the main concepts of modern physics—of relativity, quantum mechanics, and statistical mechanics, the three pillars of modern physics. To do this, students can focus on conceptual puzzles that each theory raises. For example, Erwin Schrödinger famously captured one oddity of quantum mechanics by showing how the formalism implies that a cat enclosed in a box could be both alive and dead at the same time (in a “superposition”), and that whether the cat is dead or alive will depend upon an observer looking. In the case of relativity, simple algebraic manipulations, and a focus on special as opposed to general relativity, raises a number of conceptual puzzles that can be reinforced with intuitive illustrations. Taking this all into account, then, a student coming out of the physics colloquium should be able to articulate where physics currently stands, and he should be able to tell a story as to how we got here, from Ancient Greece to today.

Start your application here: https://nsa.edu/academics/undergraduate