Back to blog

Education

February 17, 2025

President’s Day and the Order of Time

How the American calendar shifted from church feasts to civic commemorations

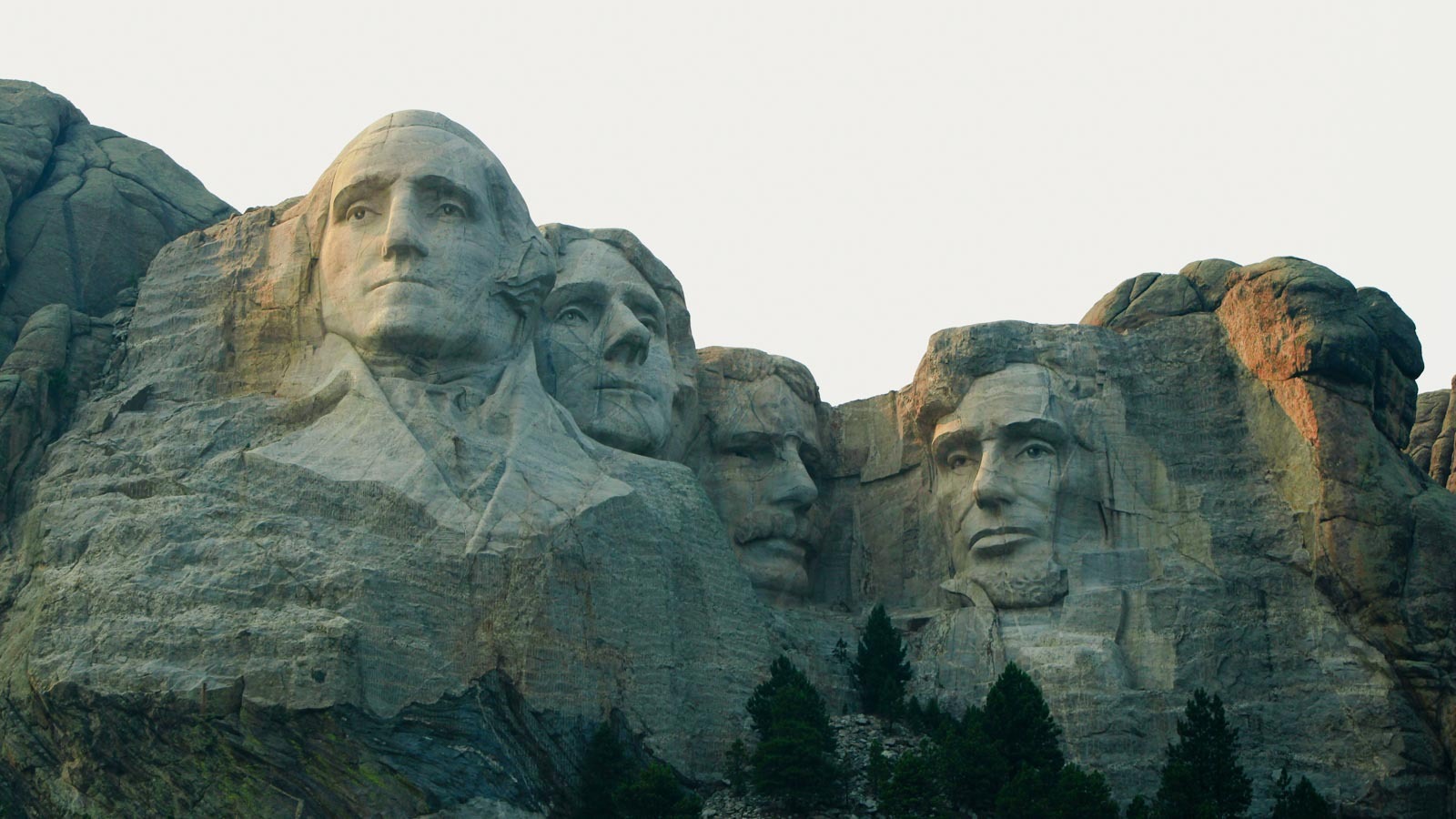

Idaho is one of eight states that will recognize “President’s Day” on Monday. The origins of the holiday trace back to a time just after the Civil War, when Congress closed federal offices for a day to mark the anniversary of George Washington’s birth. Today, six states refer to the holiday officially as “Washington’s Birthday,” and in Virginia, our first president’s birthplace, it is called “George Washington Day.”

What about Idaho’s observance? The “President” in Idaho’s “President’s Day” (singular noun) is George Washington. But in eight states plus Puerto Rico, the holiday is “Presidents’ Day” (plural noun). Students—take note of these important apostrophes! The plural noun indicates more than one president: in some cases, acknowledging Lincoln alongside Washington; in others, the aim is to honor each and every US president, as if to commemorate our nation’s pioneering scheme that organizes governmental power into three separate branches. In our neighboring Montana, the holiday is “Lincoln’s and Washington’s Birthday;” Minnesota reverses the names, there it is “Washington’s and Lincoln’s Birthday.” Colorado and Ohio deem it “Washington-Lincoln Day,” with a hyphen, but Utah uses a conjunction: “Washington and Lincoln Day.”

We can no more ignore time than we can ignore nature itself—the physical ground we walk upon, the sea, plants and animals, and especially the sun, moon, and stars. Time is ordered.

The practice of designating holidays is a gloriously human thing, a practice that arises out of the very fabric of reality. In the biblical creation account, we see how time is marked out: “the evening and a morning were the first day,” “the evening and the morning were the second day,” and so on. History’s first week dazzles us with the appearance of new sun, moon, stars, seas and dry land, plants and animals, man and woman. It should also dazzle us with the attention given to time. In creation, God gathered evenings and mornings into days. He grouped seven of those days a unit we call the week, and He set apart the seventh day and called it holy. Also in history’s original week, God showed us that time shall also be ordered in units lengthier than days and weeks, for on the fourth day He created lights in the firmament—the stars—for marking out seasons and years.

We can no more ignore time than we can ignore nature itself—the physical ground we walk upon, the sea, plants and animals, and especially the sun, moon, and stars. Time is ordered. For this reason, calendars are every bit as basic to the human experience as other aspects of our lives—marriage, eating and drinking, labor and rest. Ordering time is inescapable.

Not only does it matter that we order time, it matters how we go about it. In Leviticus 23, we find God instructing His people to mark time in specific ways. Thus, He appointed various feasts throughout the year: Passover, Firstfruits, Pentecost (or Feast of Weeks, Trumpets, or Rosh HaShanah, Atonement (or Yom Kippur), Tabernacles, whereupon time cycles back around to Passover. In Esther 9 we read that Mordecai established yet another feast called Purim. Later, in the intertestamental period, the Jews established the festival of dedication, or Hanukkah, honoring the rededication of the temple after the Greeks had defiled it. The Apostle John informs us that Jesus participated in Hannukah (John 10:22-23)—which indicates that Jesus observed a religious holiday that was not specifically decreed in scripture.

All people everywhere assign names to hours, days, weeks, seasons, and years. The way we name time invariably reveals a good deal about what we value, and about how we perceive reality. For instance, when we mark out birthdays and wedding anniversaries, we celebrate important truths about the created order. When Julius Caesar named the fifth month in the Roman calendar after himself—when quintiles became July—he presumptuously asserted his own god-like preeminence over time. The Emperor Augustus followed suit with August.

In the early years of our own nation, Americans celebrated important occasions just as people always do. These were local observances, usually called by religious authorities. It was not until the late 1800s that it became common for governing bodies to declare annual, civic holidays through formal legislative action. Idaho’s President’s Day, and its variations in other states, reflect this trend. This 19th-century development signals a the sacralization of civic life in America, the notion that our most sacred ties are forged not within our church communities, but within our political communities. Social belonging means belonging not to a church, but to the state; and “my people” refers more to my fellow countrymen than to my fellow churchmen.

The British underwent a similar transformation in the Tudor and Stuart eras, when civic observances, promulgated by monarchs and ministers in London, gradually supplanted traditional, localized religious festivals. The trend began during Elizabeth’s reign, when church bells rang annually to commemorate her coronation on November 17 (“Crownation Day”). Before long, many more national remembrances entered the calendar. Important examples include the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, the deliverance from the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 (November 5; “Gunpowder Treason Day,” and later, “Guy Fawkes Day”), the return from Spain of unmarried Prince Charles in 1633, the execution of Charles I, the Restoration (the accession of Charles II, or “Royal Oak Day,” celebrated on May 29th), among other Stuart-era milestones. In each case, royal politics penetrated ever more deeply into local lifeways. Accordingly, many Englishmen came to reckon their own community affiliation less through local relationships and more by their ties to the crown. Other Englishmen grew disgusted by the trend. Among them were Puritans who famously sailed away from their homeland and set up a “city upon a hill” in Massachusetts Bay.

As we honor President’s Day, we should note the significance of naming a figure like George Washington, a Virginian, as an official hero out here in the far-western state of Idaho. By honoring this day, we should remember a cultural transformation that we underwent in the late 1800s. That was the era when our national political life gained an important foothold over our calendar, a community life that is more central and national, less local and personal; more political, less churchly.