Back to blog

Education

December 10, 2025

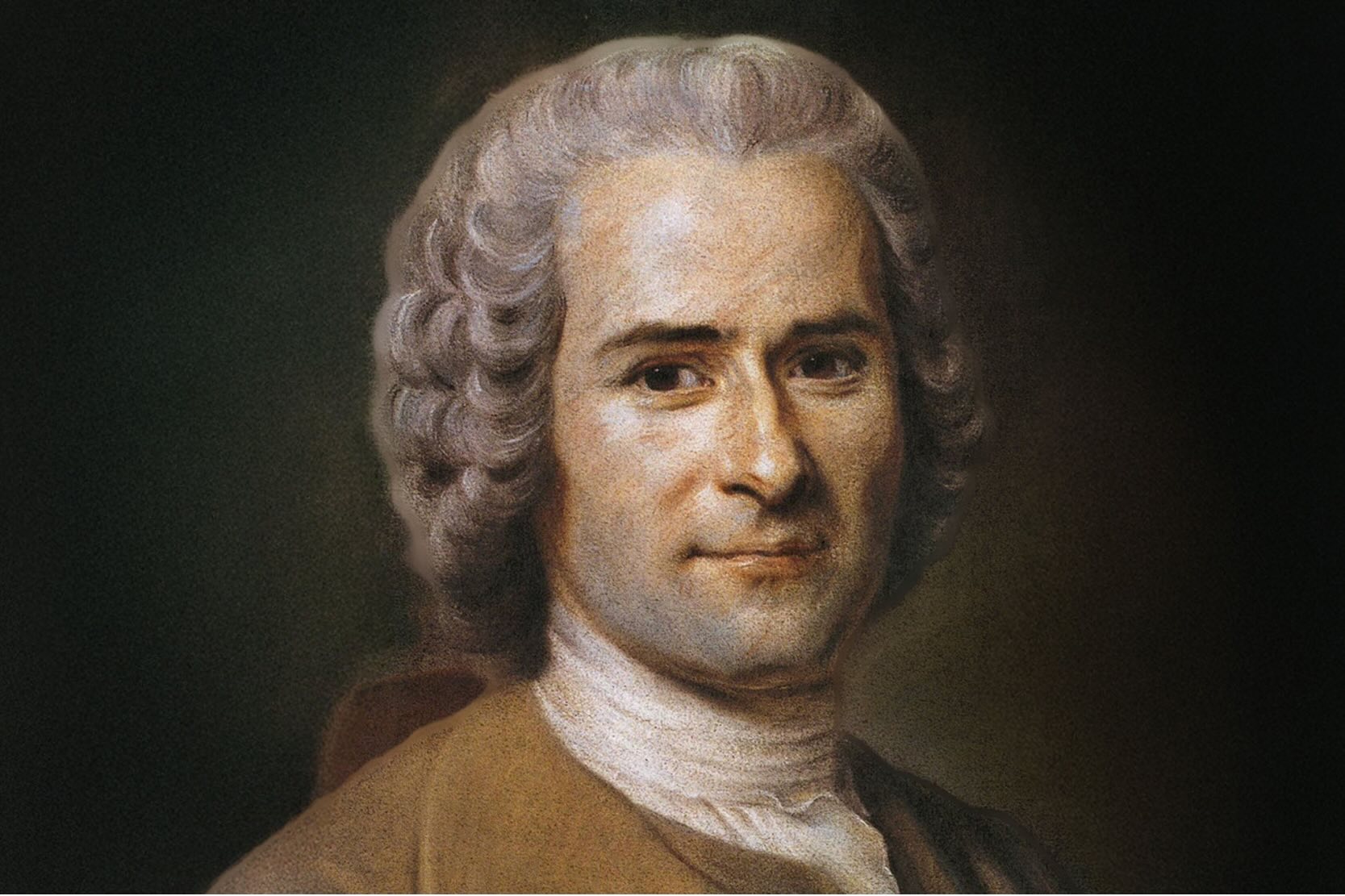

The Natural Son and Citizen of Geneva

Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Influence on Modern Politics

“If we seek the source of this stream we find first of all Rousseau, but the mythical Rousseau constructed out of the impression produced by his writings.”

Without party or partisan, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was, famously, a solitary animal. He reenvisioned the political landscape and offered a new portrait of politics and political life. Characterized alternatively as the Newton of metaphysics (Kant), divine among men (Robespierre), infantilizer of womankind (Wollstonecraft), hero of letters (Carlyle), and villain of modernity (Trueman), Rousseau is a divisive but conspicuous figure. Christians may be familiar with Rousseau’s infamous reputation, often without reading Rousseau, and he seems rather guilty by association.

It is hardly possible to approach modern politics without glimpsing some aspect of Rousseau. “All the semi-sanity, histrionicism, bestial cruelty, voluptuousness, and especially sentimentality and self-intoxication, which taken together constitutes the actual substance of the Revolution and had, before the Revolution, become flesh and spirit in Rousseau”—all this is the origin of the “fanatical head” of the Enlightenment (Nietzsche). Whether liked or loathed, Rousseau has undoubtedly imprinted himself on modernity. Everyone needs to deal with him, radical revolutionary Marxist feminists, and classically-educated Christians, too.

Rousseau anticipated his ubiquity and would not have been surprised by his mixed reception. He was aware of his “chimerical” appearance: he knew he looked different than the men around him (and different to different men). He sought to resist the monstrous portraits and unnatural tableaux that his contemporaries made in his likeness and of his thought.

To combat these depictions, Rousseau offered his readers and fellow citizens a self-portrait in his irreverently titled Confessions. At once impressed by Augustine but mystified by his piety, Rousseau writes his own in imitation of and as a replacement for Augustine’s work. The more Rousseau seems to clarify his image, the more he abandons himself to the “motley of various hues” that strike his reader’s eye. This is “the spirit” in which Rousseau intends for his portrait to be seen.

Any reflection, then, on Rousseau’s reception and influence must account for Rousseau and Rousseau. That Robispierre made him the figurehead of the French Revolution ought to be considered alongside Rousseau’s own claim that Calvin was a legislative “genius,” whose “memory” among the citizens of Geneva and inheritors of his “wise edicts,” would never “cease to bless” whatever “revolution time [might] bring about.” That Derrida used Rousseau and his writings to found “deconstruction,” a method important to critical theory, must be understood in light of Rousseau’s own motto: vitam impendere vero.

Rousseau, for example, may be the source of feminism—but only as the final provocation. His defense of inequality and difference between the sexes occasioned Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a rather negative review of Rousseau’s Emile. It’s not that Rousseau really isn’t so bad or that he has his good points and his radical ones but rather that he is implicated in a variety of contradictory ideas and movements.

It’s not enough to be classically minded, Genevan, and anti-feminist. Rousseau was all of these things, after all.

Rousseau’s Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, the first text of his philosophical and political system and the work that made him famous, challenges enlightenment prejudices by arguing that the so-called advancement of the arts and sciences does not lead to progress in morals but, on the contrary, appears to contribute to their decline. Modern man is not better than his forefathers; he is hardly a man. Rousseau characterizes the age of Enlightenment not as an age of epistemological and moral progress but of effeminacy and indulgence. Robespierre transforms Rousseau’s critique of soft lands and soft men into a violent revolution against the Ancien Régime on modern Enlightenment principles. One does not wish so much to return to Rousseau himself as to return to the classical roots of any argument against progressivism in the arts and sciences or in morality and knowledge.

Rousseau’s distaste for the mores of his own time is not the sentiment of a peaceful creature, longing to return to the woods. On the contrary, it is Rousseau’s political vision of a republic populated by citizen-men that informs his judgment. His vision of the family in society, imagined in his Emile, allocates separate and complementary roles to men and women, where wives submit to their husbands as helpmates and attend principally to their homes and children. Wollstonecraft criticizes Rousseau for thinking that “with respect to the female character, obedience is the grand lesson which ought to be impressed with unrelenting rigour.” In her view, Rousseau wrongly believes that the moral character of women is “connected with man as daughters, wives, and mothers,” and “estimated by their manner of fulfilling those simple duties.”

For Rousseau, man is the author of his own misery and men everywhere perpetuate this state of injustice and immorality. Man is in need of a Savior. Rousseau’s solution, however, is not to look for salvation in Christ but in man himself. Rousseau is often blamed for our current moral sickness. Rousseau is indeed responsible but not in a simple or straightforward way. The caricature of the noble savage, the romantic, the sentimental psychologist of the self, the compatriot of the proliterate, the revolutionary, and so on, touch on but obscure the Rousseau’s Rousseau, who is himself much more insidious in his desire for the things of God without God.

It’s not enough to be classically minded, Genevan, and anti-feminist. Rousseau was all of these things, after all. Readers should also see Rousseau as a kind of corruption of classical Christianity and not just as an avatar of modernity. Rousseau’s Christless classical Christianity, with its Spartan citizens and citizennesses and its divine legislator and its public pieties and patriarchies, cannot be overthrown by Wollstonecraft and her party but must be overthrown by the genuine article. That begins with reading Rousseau seriously and not just seeing his shades; his own appearance might be more ghastly still.