Back to blog

Education

January 11, 2023

How Federal Money Started

June 22, 1944

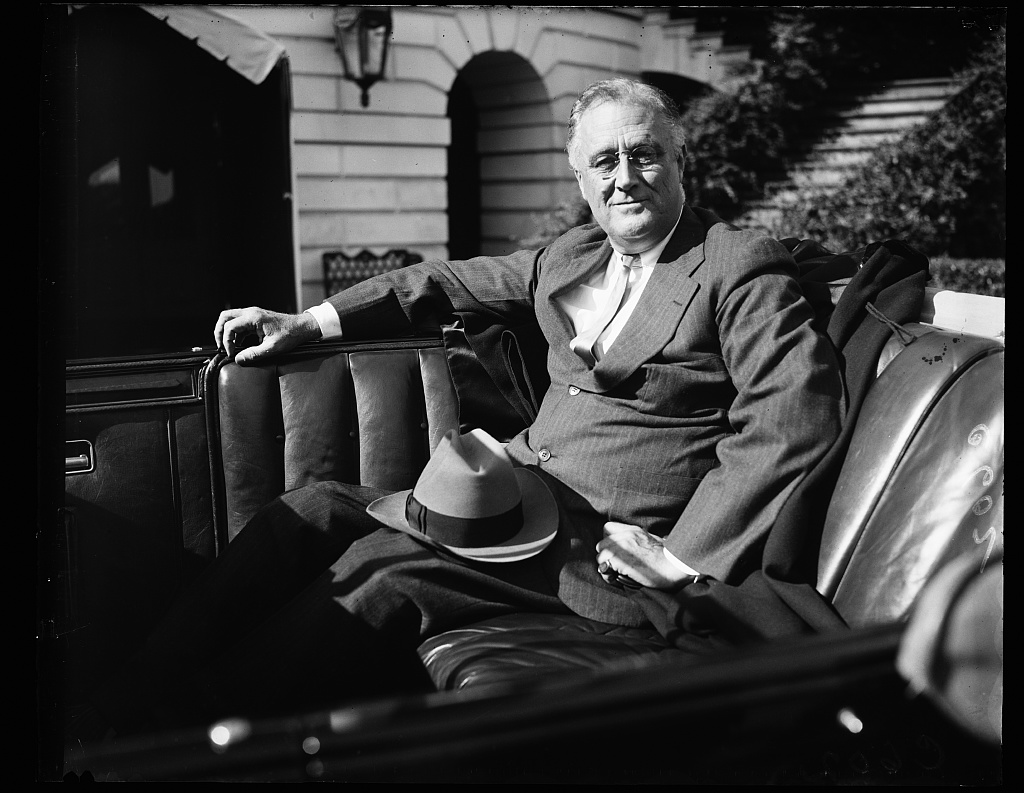

On June 22, 1944 President Franklin D Roosevelt signed the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act, now commonly known as the GI Bill. This legislation provided unemployment insurance, funded home loans, and provided tuition assistance – all for veterans returning from the battlefields of World War II. Veterans’ benefits had been a heated subject in the prior two decades – most notably in 1932 when a crowd of 43,000 World War I veterans, nicknamed the “Bonus Army,” marched on Washington DC to demand that the government pay them the bonus that they felt was due to them for their service. The Bonus Army protest eventually grew so rowdy that President Hoover had to bring in General Douglas MacArthur and his troops to drive the protesting veterans out of the capital with tanks and machine guns, burning their camps behind them. This episode proved to be a massive publicity disaster for Hoover just before the 1932 election and put the nail in the coffin of any hopes he had of serving another term as president.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, who defeated Hoover in that election, learned a lesson from Hoover’s mistakes and, in the waning months of World War II, moved swiftly ahead with a plan to avoid such a spectacle with the new wave of returning veterans. His GI Bill was rich with benefits to ensure that the veterans would truly feel the gratitude of the nation. By offering a college education and the chance to purchase a home, the GI Bill catapulted a generation of young men from the Hoovervilles of the Great Depression just prior to the war to the middle class of Ward and June Cleaver that epitomized 1950’s America. The creators of the GI Bill radically underestimated its popularity, initially projecting that a mere 7-8% of the returning servicemen would take advantage of the bill’s education benefit. The reality proved to be much higher. In 1940, roughly 500,000 students attended college in the United States. But in 1944, with the advent of the GI Bill, this number more than doubled to 1,150,000. By 1954, enrollment had climbed to 2,450,000. And in 1960, total college enrollment had grown to 4,000,000 in a short sixteen years (Matthew Fuller, ‘A History of Financial Aid to Students’, Journal of Student Financial Aid, 44.1 (2014), p. 52.)

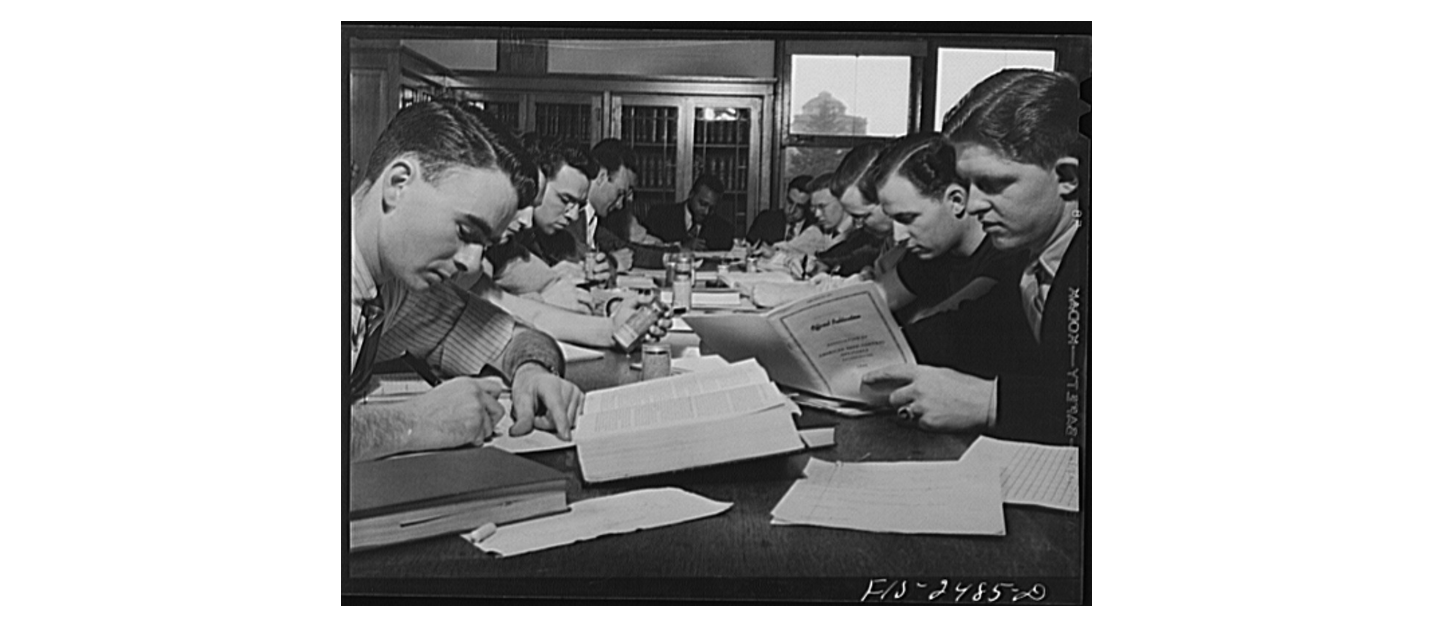

Colleges and universities across the US doubled, tripled, and quadrupled in size in a very short time as the federal government opened the floodgates of what for the students felt like opportunity and for the schools felt like the mother load of revenue streams. Early critics objected that colleges were bilking the system, overcharging to pull in as much of the federal money as possible (Fuller, p. 51.) Others were concerned about the quality of the education that the government was getting for its money. Nevertheless, the GI Bill set a precedent for the funding of colleges that, for good or for ill, catapulted the federal government into the position of being a chief funding source for higher education in the United States.

June 23, 1972

On June 23, 1972, President Richard Nixon signed the Education Amendments of 1972, which amended Johnson’s Higher Education Act of 1965. Included in this legislation was an overhaul of the federal government’s strategy for assisting with college tuition, which was determined to come in two forms – grants and subsidized loans. These funds were all detailed under Title IV of the Higher Education Act and thus federal aid for college students is still often referred to as Title IV Money.

First, the foundation for all aid to needy students was to be a grant paid by the government directly to the student. These were first called the Basic Educational Opportunity Grants, but they were later renamed “Pell Grants” in honor of Senator Claiborne Pell who was the main force behind the 1972 legislation. Students qualify for Pell Grants by demonstrating financial need on the FAFSA form (Free Application for Federal Student Aid). In the 2017-18 academic year, the federal government awarded $28.2 billion through Pell Grants to approximately 7,000,000 students (about 32% of the undergraduate population), with an average award of $4,010. This total number is actually significantly trimmed down from 2010-11 when, under Obama, the total Pell Grant award peaked at $40 billion and 37% of undergraduates were receiving Pell Grants (Trends in Student Aid 2018, pp. 27–28.)

The second piece of financial aid in the Education Amendments of 1972 was the federally subsidized student loan, initially advanced as the Guaranteed Student Loan. Students were offered loans, paid directly to the student, with the federal government acting as the guarantee for the loan and covering all interest on the loan until the student completed college. And though the Pell Grant was meant to be the foundation of student aid, the student loan has quickly taken over as the largest piece in the financial aid package. A total of 69% of the graduating class of 2018 completing their bachelor’s degree, walked out of college carrying student loan debt, with the average debt total of $29,800. And an additional 14% of their parents went into debt to help their kids with their college expenses with the average parent carrying $37,200. It is a significant gamble to start going down the path of student loans if you consider the fact that only 60% of students enrolling in college will actually graduate with a degree. This means that you have a 40% chance of taking out debt on a degree that you will never see.

Since the federal government acts as guarantor of the loan, student loan debt is some of the easiest debt to acquire. Whereas most lenders for other kinds of debt want to see financial means to repay a debt, you qualify for a student loan by showing a lack of financial means. It is easy money dished out to an eighteen year old who has not always mastered the art of fiscal responsibility. And that lack of discretion shows. About 60% of the recipients of student loan awards opt to take out the maximum amount (Fuller, p. 55.) 2.5 million American graduates owe more than $100,000. And an elite 101 Americans who owe more than a million dollars each in student loan debt.

The history of federal money in Higher Ed is eye opening. What began as a well-intentioned thank you to World War II veterans has slowly led to our current situation where the federal government is the primary patron of our institutions of higher education. And, as we will see in future posts, the federal government’s outsized role in funding America’s colleges and universities has resulted in a similarly outsized role in shaping these institutions’ final product. A desire to be free of this entanglement has led colleges, like my own New Saint Andrews, to refuse all Title IV money. As my friend Robert Bortins has said – “If you take the shekels, you get the shackles.”